Ensuring A Healthy Population Should Become A National Priority And Our Objective for Reforming Our System

All developed nations focus on keeping their populations healthy and provide identical universal access to healthcare for all.

The United States alone does not. On the contrary we use insurance to ration access to care based on ability to pay. We then try to correct this fundamental flaw by subsidizing various groups who can’t afford the premiums. Accordingly, the system that has been created, or more accurately evolved, is riddled with unproductive middlemen, mind boggling complexity, misaligned incentives, unfathomable cross subsidies, and is by far the most expensive and ineffective in the world. The complexity is, in and of itself, a major impediment to controlling costs and a major obstacle to reform. Successful reform will require us to change the way we think about providing access from a good to be purchased like, for example, automobile insurance, to a national priority at an equal level with financial integrity and national defense.

Sensible Healthcare Reform is a comprehensive program for reform that is based on an evidence based definition of the problem. The clear objective is...

“to continually improve the health of all Americans

while systematically reducing national healthcare spending”

This objective cannot be achieved simply by incremental changes to our existing system. Treating the health of the nation as a national priority leads directly to the conclusion that healthcare insurance is superfluous and direct subsidy (which eliminates the need for insurance companies and all the other middlemen they have spawned) is much more efficient, effective and affordable. As a national priority, the same level of access to healthcare should be provided for all Americans and funded by the federal government from general revenues.

Providing efficient and effective access to care is only part of the challenge of ensuring a healthier population. The Medicare Trust is projected to run out of funding by 2028. This is largely driven by the high incidence of chronic disease driven by unhealthy lifestyles and exacerbated by our aging population. These exogenous factors will continue to drive national healthcare expenditures. Our very successful programs to stigmatize smoking are illustrative of the initiatives required. While there are numerous government programs to promote heathier lifestyles, progress is extremely slow. The use of preventive medicines to control the early onset of such serious lifestyle related problems as obesity, alcohol and drug abuse, dementia and heart disease should also be aggressively promoted.

There is no way to fix our broken healthcare system without first eliminating the unnecessary and counterproductive costs that exceed one-third of our total national spending on healthcare -$4.3 trillion in 2021.

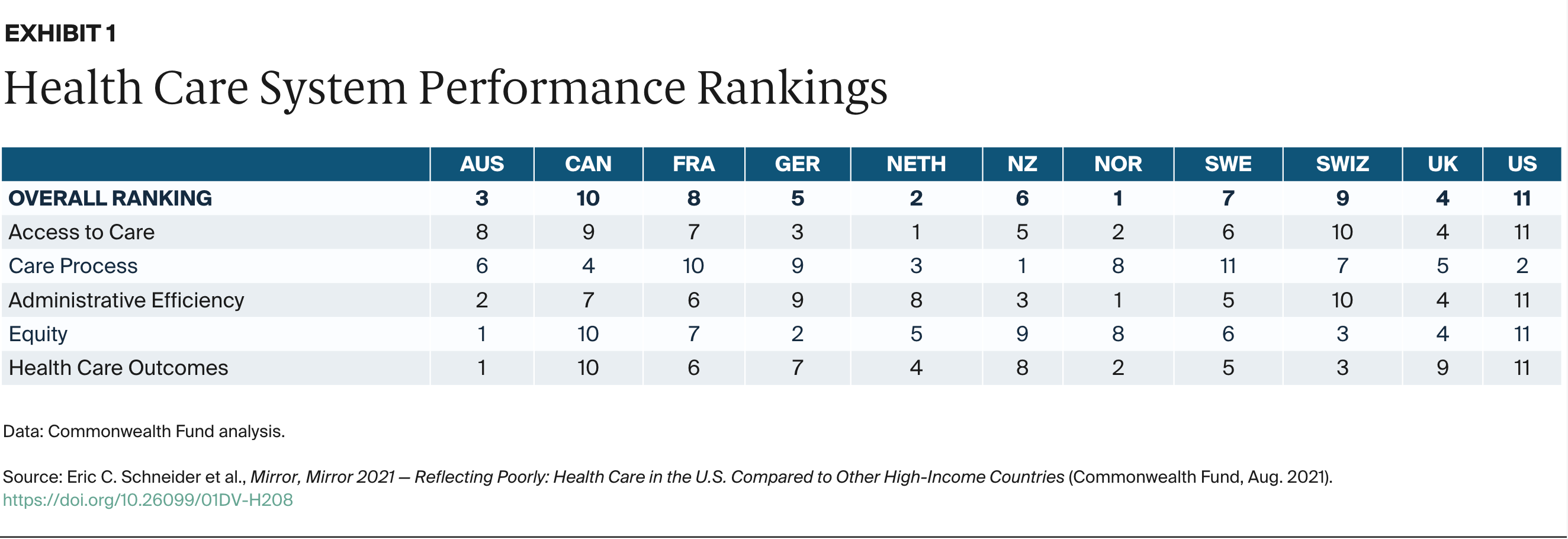

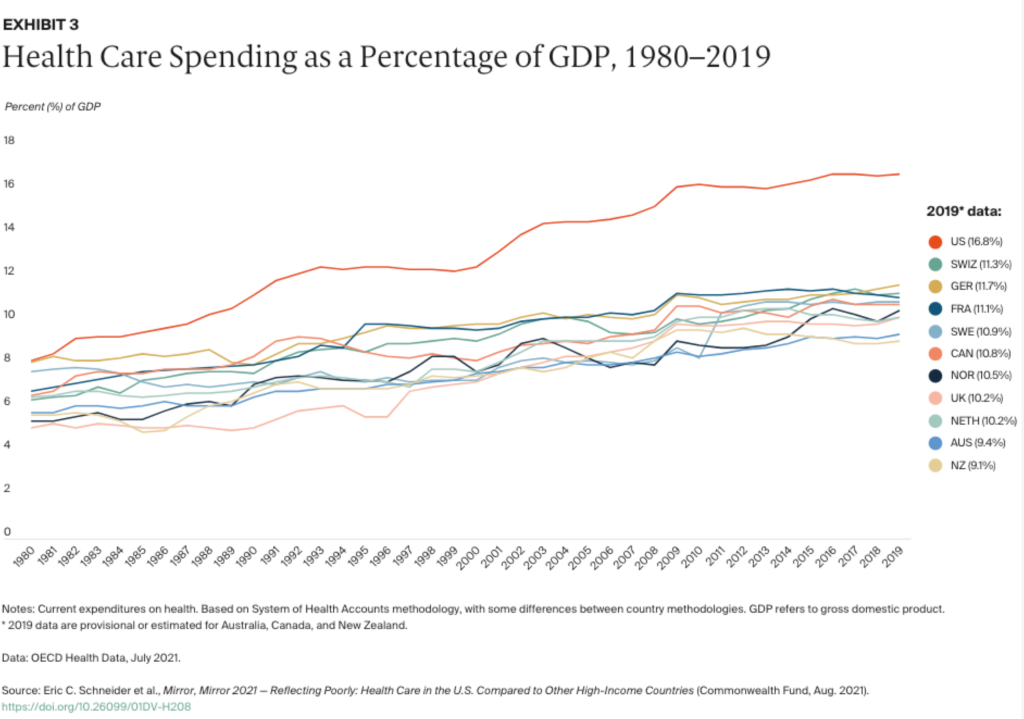

The Commonwealth Fund has captured the state of US healthcare in two charts

https://infogram.com/mirror-mirror-2021-exhibit-1-1hdw2jp0qzlqj2l

https://infogram.com/mirror-mirror-2021-exhibit-3-1h7k230dkllmg2x

* * *

The purpose of this website is to provide a more complete exposition of the case for a federally funded single-payer health care system. The section below, Rationale and Recommendations presents an evidence-based argument for moving to a federally funded single-payer system. The other home page tabs include additional explanatory essays, sources, international comparisons, and a strategy for transitioning smoothly to a federally funded single-payer system. The tab Unhealthy Lifestyles and Aging highlights the potential for chronic disease that places ever more pressure as our population continues to age.

Rationale and Recommendations Prioritizing The Health Of The Nation With A Federally Funded Single Payer System

After nearly fifty years of experience with healthcare issues, I am convinced that the way we think about paying for healthcare is wrong. Medicare is now scheduled to run out of money in 2028 and President Biden is proposing to refinance it by raising taxes and manipulating drug prices. This will only exacerbate the problem of annual increases in our total spending on healthcare and diminish our ability to pursue more effective treatments for chronic disease. It is time to fundamentally change the way we pay for medical care, make the health of our population a national priority, and eliminate the unproductive costs of the complexity of our system which have driven healthcare spending to almost 20% of GDP. Providing an identical level of access to healthcare and funding it from general revenues will do just that.

Ever since joining the Board of New York Hospital in 1975 I’ve been actively involved in the provision of healthcare in the United States. I’ve also been thinking deeply about healthcare reform since 2006 when I became a member of a Brookings Institution advisory panel on the federal budget deficit. My interest and understanding of healthcare have been further nurtured as a board member of Amgen, lead director of HCA, Board Member of Rand Health, and the Cottage Health Care System of Santa Barbara, and as the founding Chairman and CEO of CytomX (Nasdaq) the pioneer in conditionally activated cancer therapies.

Quite naturally, I’ve tracked the efforts of our nation to provide high quality, cost-effective equal access to medical care. These efforts have had mixed success; incrementally improving access while costs continued to escalate faster than GDP; an unnecessary drag on the rest of the economy. Moreover, a recent Associated Press NORC poll reported that the majority of Americans are unhappy with our healthcare system and almost 8 of 10 are “moderately concerned” that they won’t be able to get necessary care when they need it. The New York Times recently published a guest editorial highlighting the discouragement and demoralization which is endemic in physicians and their coworkers.

Meanwhile many hospitals and physicians are struggling with their finances while the health insurance companies, and an agglomeration of other middlemen, are prospering. Something is seriously wrong with our system.

The fundamental problem is we equate health care with healthcare insurance and our systems both public and private are insurance based and marketed much as a differentiated consumer product with a wide range of choice. We have to move on from treating healthcare as a good to be purchased like, for example, automobile insurance, to a national priority on the same level as defense and financial stability.

Much of my experience in this arena has been connected with large corporations, including many years leading McKinsey and Co. It may therefore surprise you to learn that I have concluded that what we need is a single-payer system. I’d like to explain why.

Five unshakeable facts define the problem.

- Private insurance rations care based on ability to pay and is dramatically more expensive than a direct-subsidy system. It has administrative costs proportional to the amount of healthcare delivered, plus the costs of a complex insurance and reimbursement structure and the middlemen it spawns. The US has the most extensive middleman structure in the world. On the other hand, a single-payer system has administrative costs that are proportional only to the amount of healthcare provided.

- The costs of this complexity reach into every nook and cranny of the economy. A detailed and comprehensive study by the National Medical Library (NML) in 2014 estimated billing and insurance (BIR) costs in the US health care system totaled approximately $471 billion in 2012. This includes $70 billion in physician practices, $74 billion in hospitals, $94 billion in settings providing other health services and supplies, $198 billion in private insurers, and $35 billion in public insurers. Moreover, this does not include the substantial time, energy, and money devoted to managing insurance by individual patients. Compared to simplified financing, the NML report estimated that $375 billion, or 80%, of the BIR costs of the current multi-payer system, could be eliminated. This was roughly equivalent to 15% of total spending on healthcare. Fifteen percent of 2022 spending would amount to $645 billion.

- Additionally, the lack of transparency in the way insurance is administered by providers has led to overutilization of products and services, fraud, and an insidious web of cross subsidies. Estimated costs of overutilization and fraud range from $300 billion to $680.

- Employer Sponsored Insurance subsidizes higher-income earners by paying for coverage with pre-tax dollars, which translates into over $300 billion in foregone tax revenue.

- Government-funded insurance is also unnecessarily complicated by the redundancy and complexity of multiple administrative agencies including Medicare, Medicaid, CHIP, and the Veterans Administration. For example, there is no valid reason why Medicare is federally administered, while Medicaid is a joint federal, state, and local program. This complexity is further exacerbated because each state chooses the way it will administer Medicaid, as well as how it will regulate the insurance companies doing business in that state. Moving to a federal single-payer system would eliminate this complexity and eliminate the overwhelming majority of the costs incurred by the states to administer Medicaid and regulate the insurance industry.

These estimates of unproductive costs approximate one-third of total national healthcare spending (well over $1 trillion). The foregone tax revenues drive the cost of complexity even higher. Our insurance-based system is the reason why the insurers and other middlemen prosper while costs spiral out of control, and patients and providers are financially challenged, discouraged, and demoralized.

There is no way to control our escalating costs and address the other problems noted above without addressing the enormous complexity of the way our insurance-based approach to financing healthcare has evolved. The simplest and most straightforward way to reduce complexity and reach universal access is to move away from our insurance-based system to a single-payer system. Of course, the idea of a single-payer system is not new but no argument to date has persuaded the general population, corporate America, our government, or our politicians to act.

The almost innumerable choices offered by the insurers differ primarily in terms of various forms of copay that simply determine who pays for what and when. Despite this, the private insurers market healthcare insurance much as a differentiated consumer product which requires major marketing and sales capabilities and the management of a complex billing and reimbursement system. This is not surprising since the private insurers are cost-plus businesses whose profits are regulated by the Medical Loss Ratio which simply requires 80% to 85% of premiums to be passed through to the healthcare providers; the more complex the system, the higher the premiums, the larger the amounts that stay with the insurers.

Roughly a thousand private insurance companies provide a staggering array of options; far too many for anyone to capably examine and compare. This complexity results in duplicate levels of bureaucracy, administrative expense, and hidden costs not only within the insurance companies themselves (and the other fringe middlemen that have emerged to help navigate and profit from the complexity) but also in the healthcare providers, the government regulators, and the group purchasers and individuals that must deal with it.

Most importantly, this complexity of choice has minimal effect on the amount of necessary care that is actually delivered. All healthcare insurance policies, public and private, offer essentially the same extensive coverage of diseases and other healthcare needs. This coverage was defined by the Affordable Care Act as Essential Health Benefits (EHBs). Choice has relatively little effect on the type of care one will eventually receive; they will get the standard of care chosen by their physician whether they’re either privately or publicly insured, a self-payer or the beneficiary of a safety net such as an emergency room, a neighborhood clinic, or charity care. Choice in insurance primarily determines who will pay for the necessary care when, and if, it is delivered.

One insidious exception is when people at the lower end of the income spectrum initially choose the low premium options and then forego necessary care rather than pay one or another of the various forms of copay when the need arises. This failure to seek necessary care frequently leads to development of a more serious and chronic health problem which in turn raises the lifetime cost of the person’s medical care. In effect insurance, once again, rations healthcare on ability to pay.

The Commonwealth Fund’s Mirror, Mirror report issued every 3 years compares the healthcare systems of 11 developed nations and has never ranked the US anything above dead last in overall capability to deliver quality and cost-effective care, despite spending from 50% to 100% more than the other countries. These findings are also consonant with periodic reports issued by Bloomberg and the World Health Organization. All of the other developed nations do provide equal access for all.

As noted above there is no way to control the escalating cost of healthcare (which now accounts for approximately 20% of GDP) without reducing the complexity of our approach.

So, I ask myself, why don’t we simply recognize that insurance is a very poor way to provide access to healthcare, explicitly define the role of the federal government as maintaining the health of the population, and transition to a single-payer system that will eliminate the complexity and the unnecessary spending? The existing federal organizations involved in healthcare could be dramatically downsized and consolidated into a new agency – The National Health Security Agency (NHSA) – which would be set up like the Federal Reserve to insulate it from short-term political pressures.

The two major objections to a single-payer system are cost and the difficulty of a transition.

Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All, 2022 was a directionally correct single-payer system. If implemented as outlined above with identical coverage for all and no choice, and explicitly addressed the other complexity issues, it would be less expensive than our current Rube Goldberg-like system. This conclusion has been supported by the Congressional Budget Office and also by an independent study by the Yale School of Medicine. It is also consistent with the argumentation in this essay.

A second objection is that the transition to a single payer would be too difficult and disruptive. In fact, the entire process of reducing complexity could be catalyzed by simply requiring all insurers (private and public) to provide a single, identical level of coverage with no choice and no copays. This would drive a dramatic downsizing in the private insurers by eliminating the overwhelming majority of marketing and sales expense and limiting their role to administering the much simplified reimbursement system; it would also force them to compete on price and quality of this service rather than the hollow differentiation based on ability to pay which drives unproductive complexity. The public insurers would be folded into the single-payer system.

The NHSA would oversee the transition to the single-payer system, and subsequently supervise its operations including the methods for reimbursing the healthcare providers.

Because the inefficiencies and waste are so widely distributed throughout the entire economy the disruption in any particular area would be minimized in a phased transition. The actual delivery of care would be minimally affected except that the unwillingness to seek necessary care in the face of copays would be eliminated.

The healthcare providers would remain in the private sector but would be relieved of the onerous problem of negotiating reimbursements with a myriad of insurers and the expenses it creates. The physicians and their colleagues could go back to practicing medicine and finding satisfaction and fulfillment in their professional lives. The providers would be least affected and welcome the reduced complexity in the billing and reimbursement process. The American public at large would let out deep sigh of relief when they would no longer have to concern themselves with how to pay for care or deal with the insurance companies.

Because some of the major players in health care - the insurance companies and other middlemen - are so invested in the current way things are done, addressing the costs of complexity seems to be too hot to handle for politicians on either side of the aisle. And despite efforts to improve the quality of lifestyles, progress has been limited. Thus, the impetus for change will have to come not only from outside the government but also from outside the network of vested interests. In other words, it will have to come from us, the general public, and the employers[1] who are burdened with the loss in productivity from chronic diseases in the workforce.

[1] See the Appendix for a discussion of the lost productivity because of the prevalence of chronic disease in the workforce

Appendix

Moving to a single-payer system is an absolutely necessary first step to gaining control of our healthcare costs. Unfortunately, in the longer term it will all come to naught without a concerted effort to reduce the well documented high incidence of chronic disease caused by unhealthy lifestyles. The most important are poor nutrition, smoking, lack of physical activity and excessive use of alcohol. According to the American Action forum, the prevalence and cost of chronic disease in the United States is growing and will continue to grow, not just as a result of the Baby Boomer generation aging but also due to increased disease prevalence among children and younger adults. Those with chronic disease and their families face both direct and indirect costs: Direct costs primarily stem from longer and more frequent hospital visits and greater prescription drug use, while indirect costs arise from lost education and job opportunities. When including indirect costs associated with lost economic productivity, the total cost of chronic disease in the United States reaches $3.7 trillion each year, approximately 19.6 percent of the country’s gross domestic product.

Similarly, according to John Hopkins Medicine, chronic illnesses, and injuries among the US work force cost employers billions of dollars every year due to absence and lost or reduced productivity. In fact, they estimate the total cost to employers is $530 billion. The largest portion, $198 billion is due to diminished productivity from unmanaged or poorly managed chronic health conditions. Another $178 billion is the cost of wages and benefits for incidental absences due to illness, workers’ compensation and FMLA. A smaller portion, $82 billion covers the cost of missed revenues, hiring temporary workers, and overtime. And the final $73 billion is the cost for workers’ compensation payments and related cost.

Finally, a comprehensive study by the Milken Institute concluded that the total costs in the US in 2016 for direct health care treatment for chronic health conditions totaled $1.1 trillion—equivalent to 5.8 percent of US gross domestic product (GDP). When the indirect costs of lost economic productivity, $2.2 trillion, are included, the total costs of chronic diseases in the US increase to $3.7 trillion This is equivalent to 19.6 percent of the US GDP—in other words, nearly one-fifth of the US economy.

A major public awareness campaign similar to what was done to stigmatize smoking will be essential to bringing unhealthy lifestyles under control and reduce the incidence of chronic diseases caused by, for example, drug and alcohol abuse and obesity. Similarly, the use of preventive medicines to control the early onset of such serious lifestyle-related problems as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease should be highlighted in the expanded Essential Health Benefits. Our aging population will continue to drive costs out of control unless we’re successful in these preventive measures.

Estimated Cost Savings

The unnecessary and counterproductive administration cost driven by complexity will essentially be eliminated at the insurers and throughout the healthcare system by moving to an identical level of access for all Americans. Increased transparency will allow overutilization and fraud to be systematically reduced by, for example, using AI enhanced comparisons of frequency of utilization by providers. The tax preference for Employer Sponsored Insurance will no longer be part of the system. The other middlemen and the costs of fragmented government programs will also be eliminated by the move to an identical level of access.

$0 Billion

Unproductive Admin Costs$0 Billion

Systematic Overutilization$0 Billion

Forgone Tax Revenues$0 Billion

PBMs & Other Middleman$0 Billion

Fragmented Government AdminPlain Talk About Healthcare

Plain Talk About Healthcare is a conversation between a presidential candidate and her advisor on healthcare reform that recapitulates the case for Single Payer and explores more completely the challenges of implementation.

About the Author

Fred Gluck joined McKinsey & Co. in 1967 and led the Firm as its elected Managing Partner (Global Senior Partner) from 1988 to 1994. Upon retiring from McKinsey in 1995, he joined Bechtel and served as Vice-Chairman and Director. In 1998 he retired from Bechtel and rejoined McKinsey as a special consultant to the Firm serving in that capacity until 2004.

His extensive background in health care includes serving as the presiding director of HCA as well as on the boards of Amgen, RAND Health Care, and the Cottage Hospital System of Santa Barbara. He also served on the board of the New York-Presbyterian Hospital for over 30 years before achieving emeritus status in 2006. Fred was also the founding Chairman & CEO of CytomX Therapeutics (NASDAQ: CTMX) and LungLife AI ((AIM Exchange, London). He also served as Co-Chairman of TrueVision Systems, a world leader in computer guidance for microsurgery, prior to its recent sale to Alcon.

Fred has also written and spoken on health care reform dating back to his service on an Advisory Panel for the Budgeting for National Priorities project at the Brookings Institution in 2005-2006.